Daj gryza

English title: Have a bite

co-author (recipes and research): Natalia Baranowska

Publisher: Wydawnictwo Dwie Siostry

Warsaw 2020

Dimensions: 27.2 × 37 cm

Hardcover: 112 p.

ISBN: 978-83-8150-106-4

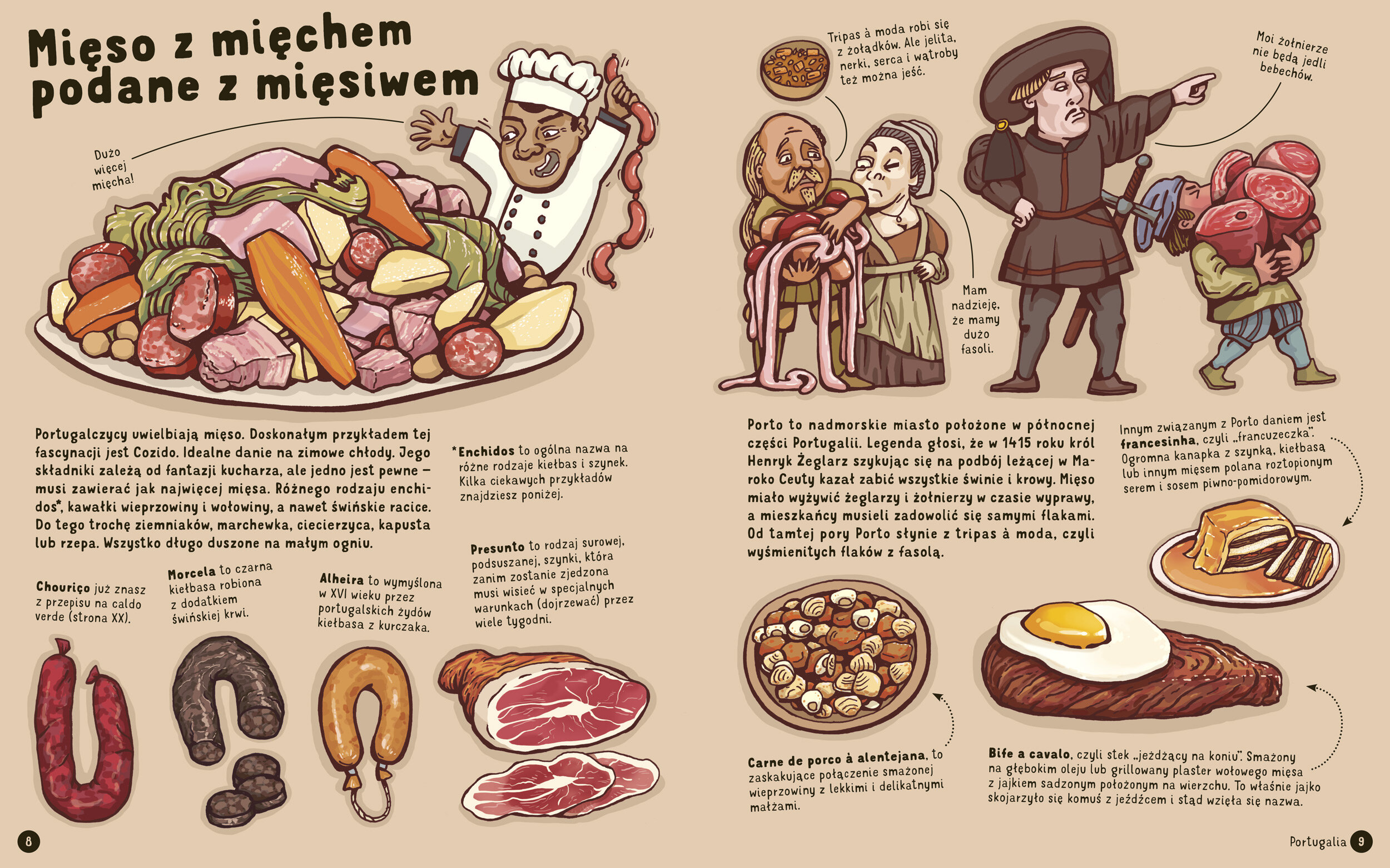

Blurb from the publisher:

Where did corn come from? And wheat? And potatoes? What people in Turkey have been eating for centuries? And in Italy? And Nigeria? How to make Vietnamese pancakes, Brazilian pralines or Hungarian lecsó? This delectable book will take you on an adventure filled with tastes, meals and ingredients. You’ll visit 26 countries from all over the world and discover their native cuisines. You’ll not only find new delicacies, but also learn about their remarkable journeys along the way. But above all, you will see how strongly food is related to the history, culture and nature.

This is our forth oversized picture book. After geography, geology, and biology it was time for some history. We wanted to show how access to different products – like wheat, rice or potatoes – enabled the rise of first civilizations, how food that travelled with traders, migrants and refugees changed local cultures. We also wanted to get a glimpse of the ever changing net of flavours and culinary habits that affect our daily lives more then we usually want to admit.

It took a while

Most of our big projects take years to finish. We’re used to it and we have our ways to keep us motivated and exited about the work. When we take on a new endeavour we’re ready to have it on our computer screens for a very long time. But this project has been occupying our minds since 2010.

Version 0.1

First, there was an idea for a cookbook. Our friend Maria Szkop had a list of great recipes that families could prepare together. We were just to add some funny drawings, a comment here and there, and a somehow realistic representation of the dish (we never use photography in our books).

We gave it a solid try and presented the outcome to the Dwie Siostry publishing house (at the time we had only 3 or 4 books under our belts). They had some objections to the general concept and asked Maria for changes she didn’t want to make. The project was cancelled, but our urge to draw food remained strong. Our only outlet for this need were small drawings of national dishes that appeared on almost every spread of the Maps book. Researching and drawing them was a lot of fun, but we knew there was an untapped potential here.

After publishing Maps we had a new idea, a hybrid of some kind. Since we enjoyed researching food from different countries, why wouldn’t we make a book about it? Maybe we could present traditional recipes from selected regions and tell stories behind distinctive ingredients or culinary methods.

We tried to find someone who would like to work with us on that project. We needed a list of about 50 reliable recipes and some help with the research. First promising co-authors didn’t deliver the needed time commitment or high enough quality. In 2014, after another year of stalling, we were frustrated and needed a new plan.

A New Co-author Joins the Battle and More Failed Attempts

At this time our best friend Natalia was on a career crossroad. In 2007 she graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw with a diploma from book design (same year and specialization as ours), but after a few years of designing she decided that food is more interesting than InDesign. I’m not sure if she knew back then what exactly she wanted to do, but reading emails from clients about colours of letters was not one of those things.

This coincidence did not escape our attention. We asked Natalia if she wanted to work with us. She agreed immediately and in March 2015 we had first spreads of the new project.

Unfortunately this version was too chaotic, didn’t have solid structure we could build on, and Dwie Siostry didn’t like the way we wanted to draw big, close-up portraits of eating people. We even made an attempt to change the portraits into drawings of ingredients, but that didn’t change the overall impression.

After that we tried to create something entirely different – a cardboard book about ingredients of popular foods for 3–4 year old children, but this idea also was turned down.

The final attempt

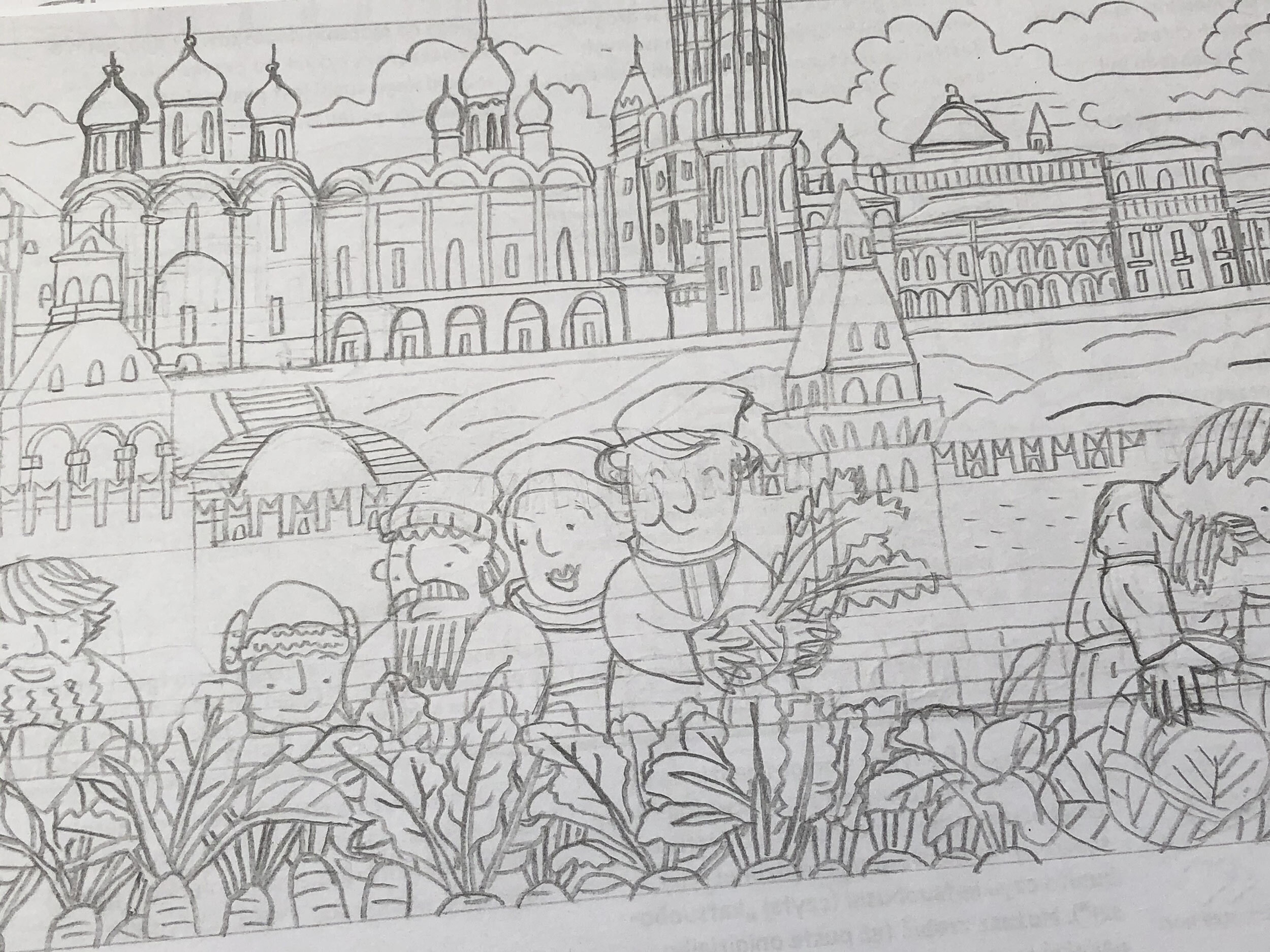

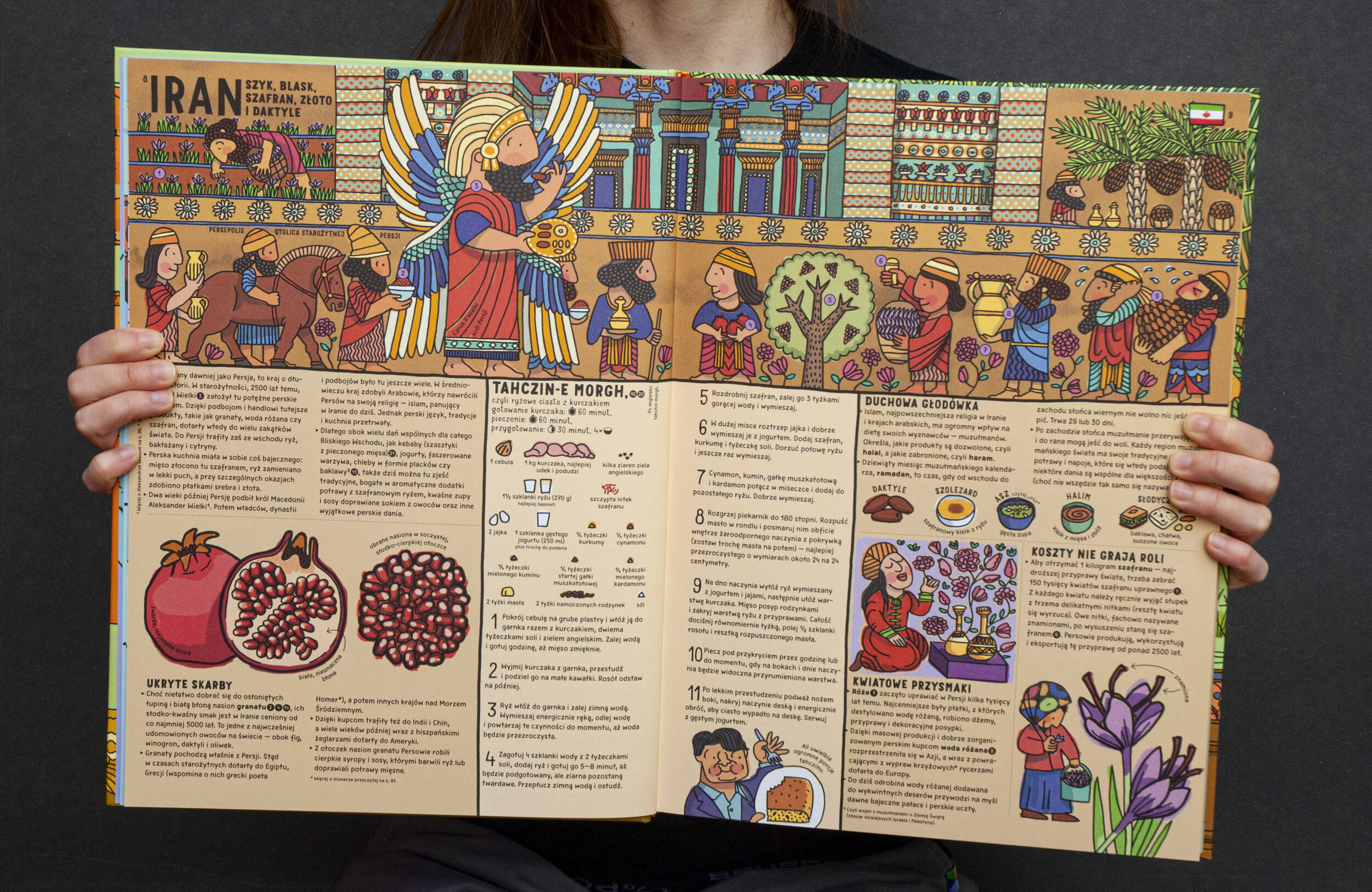

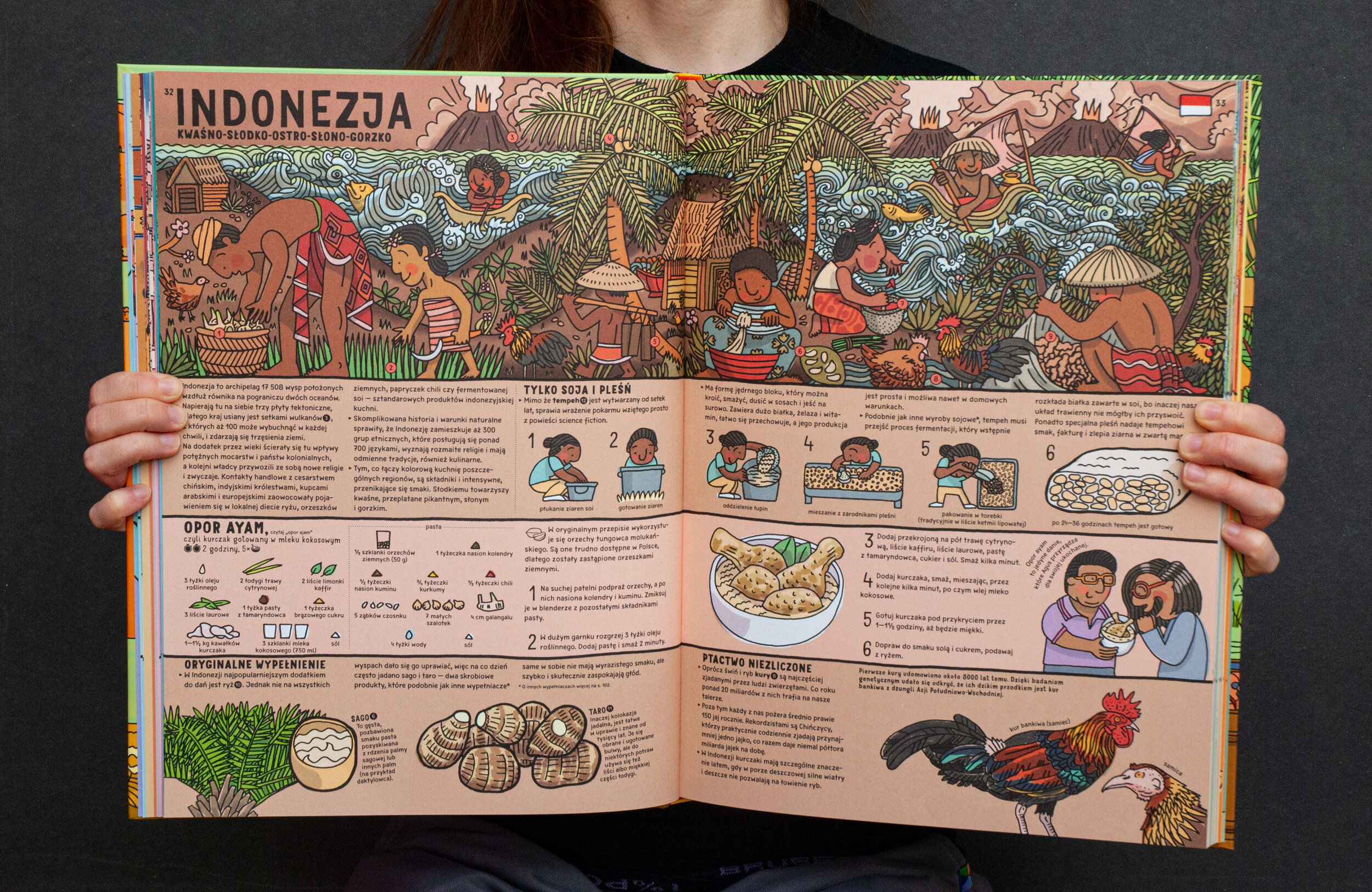

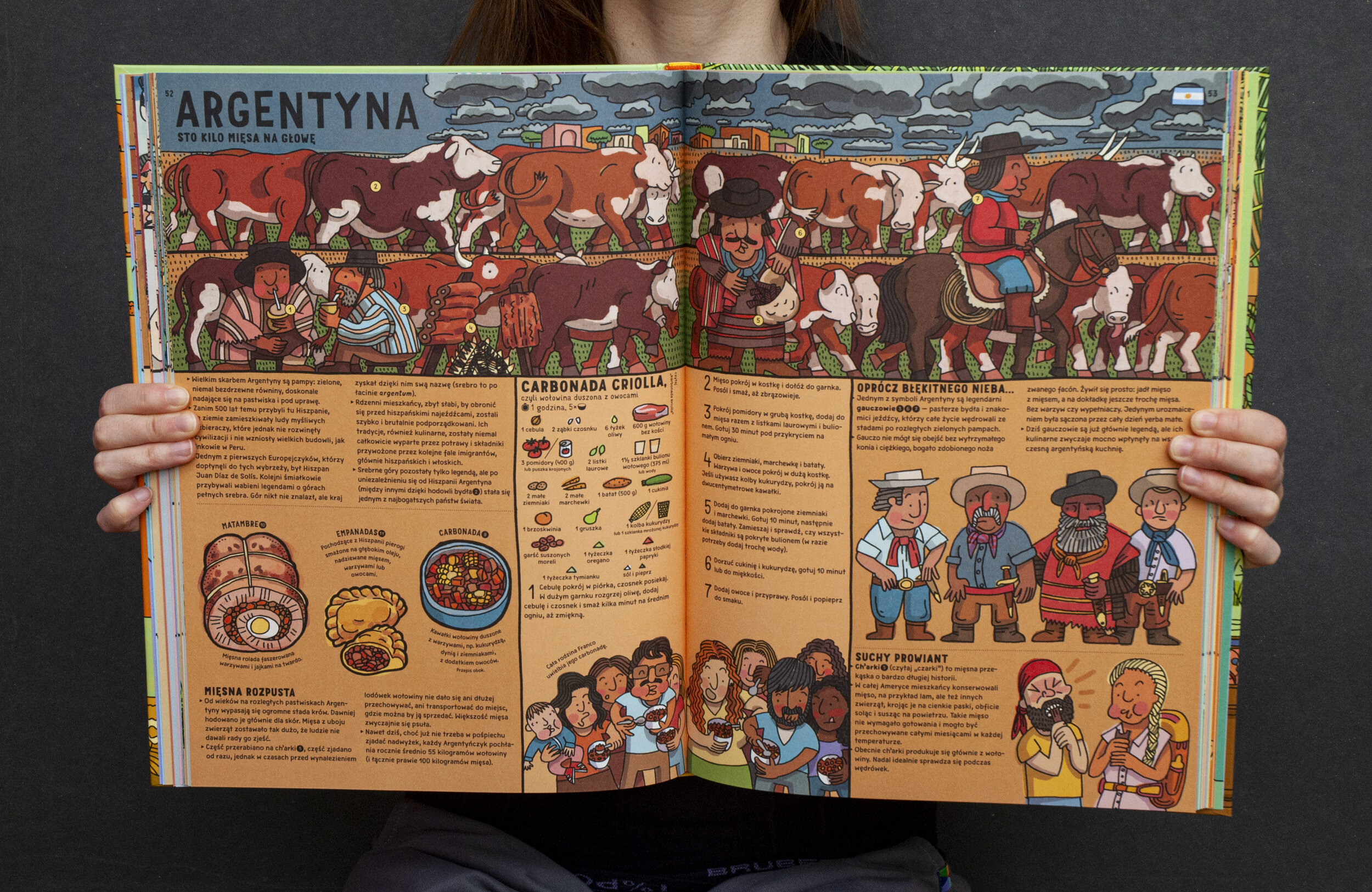

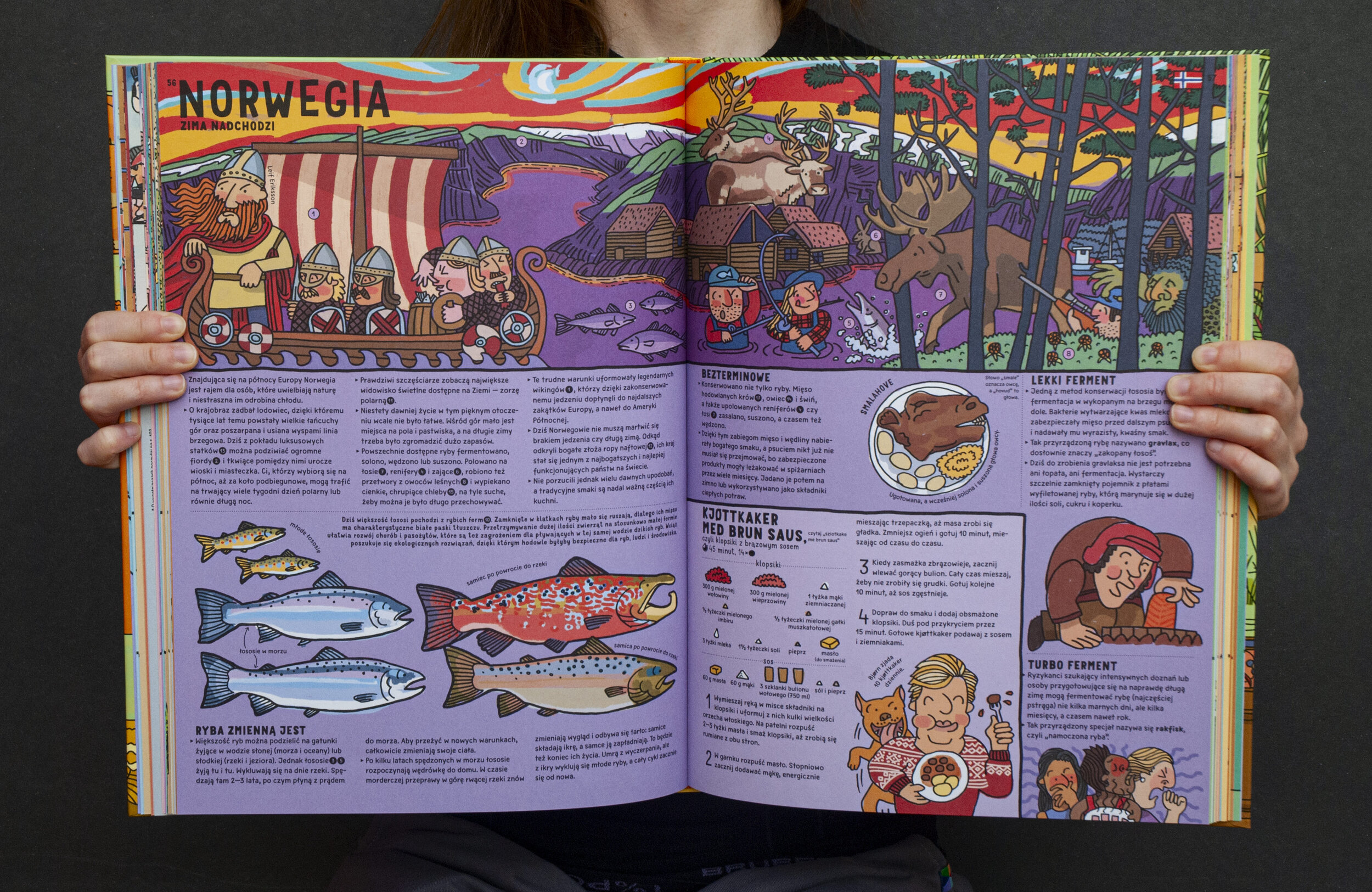

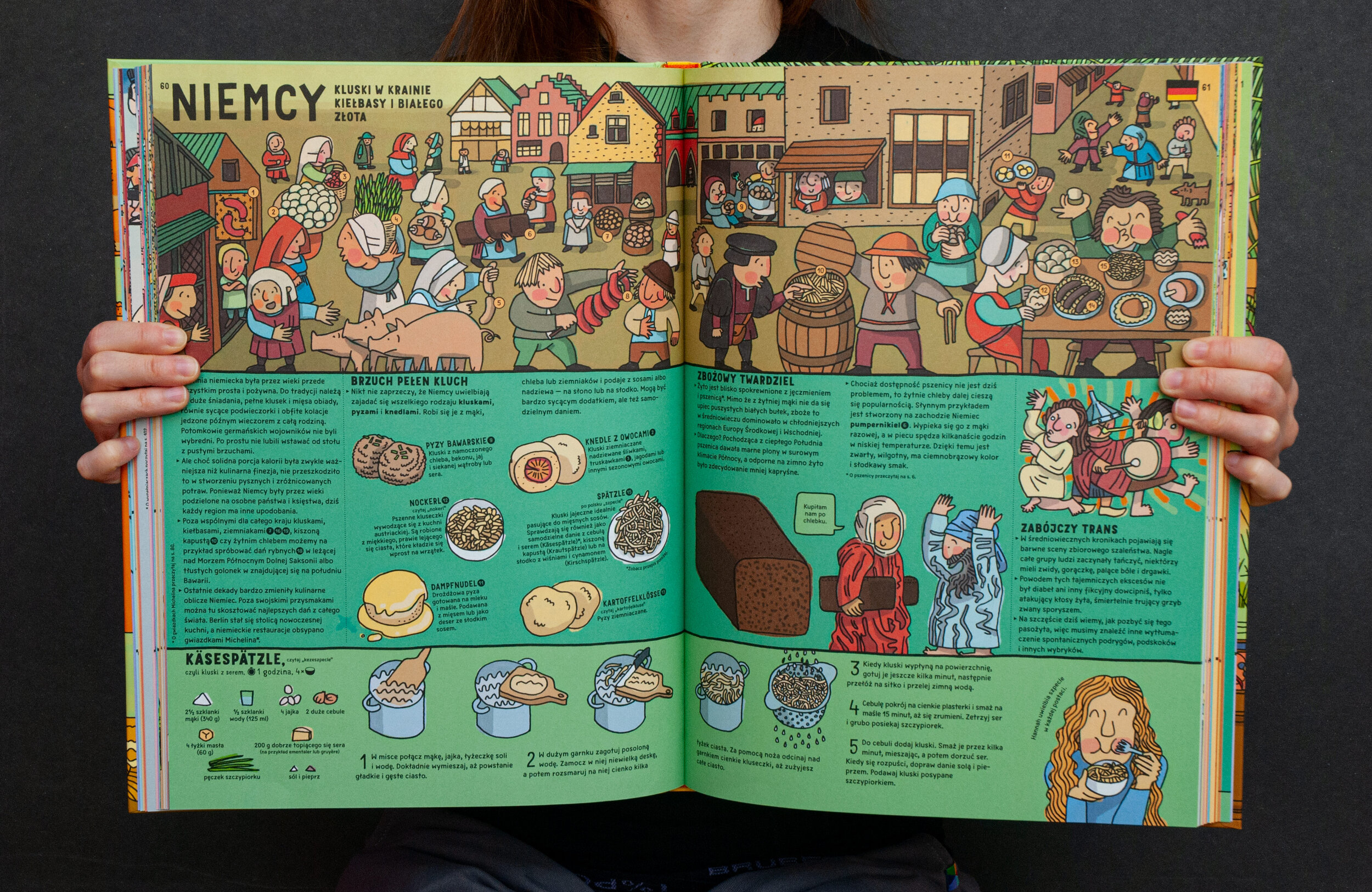

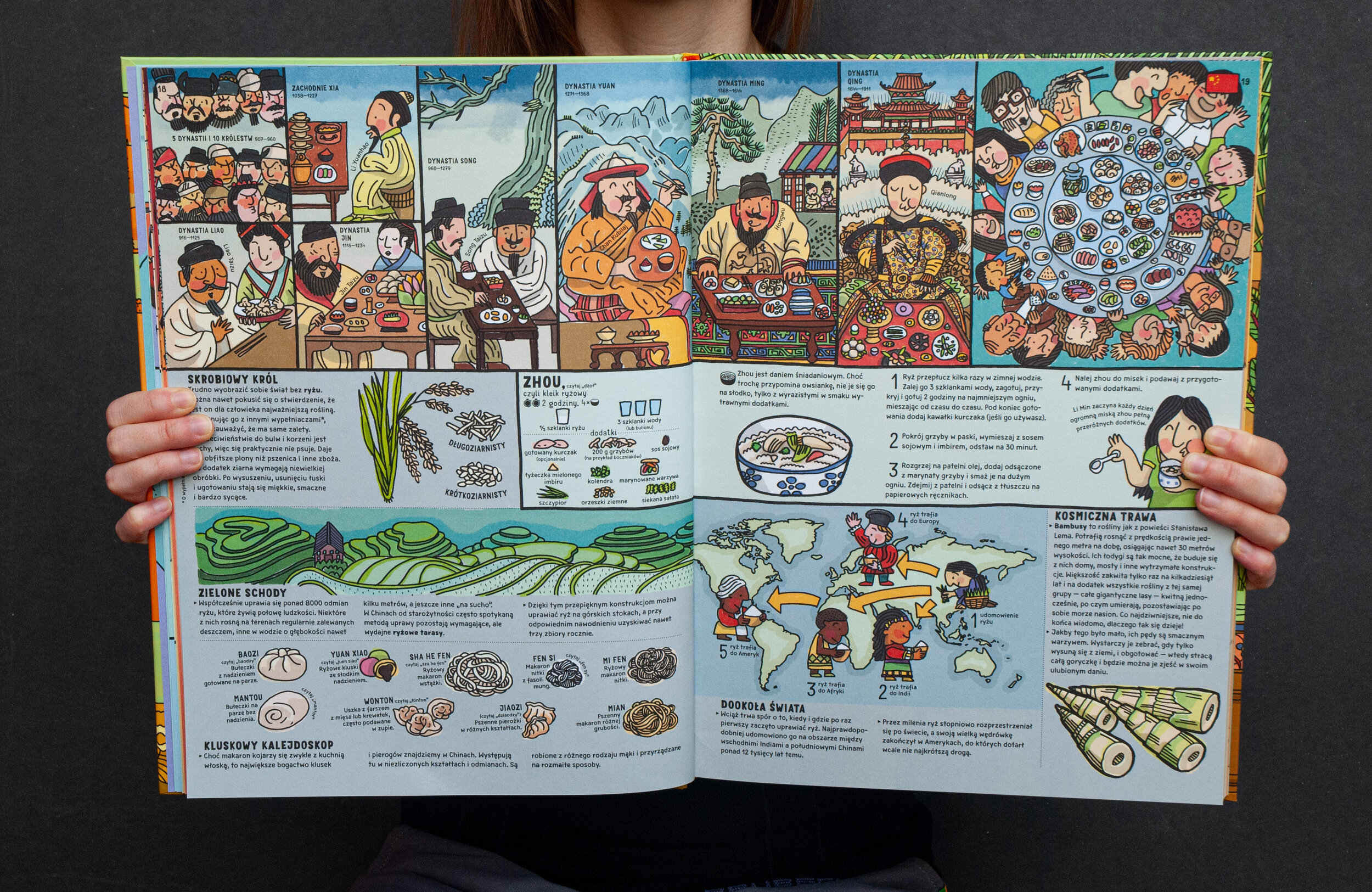

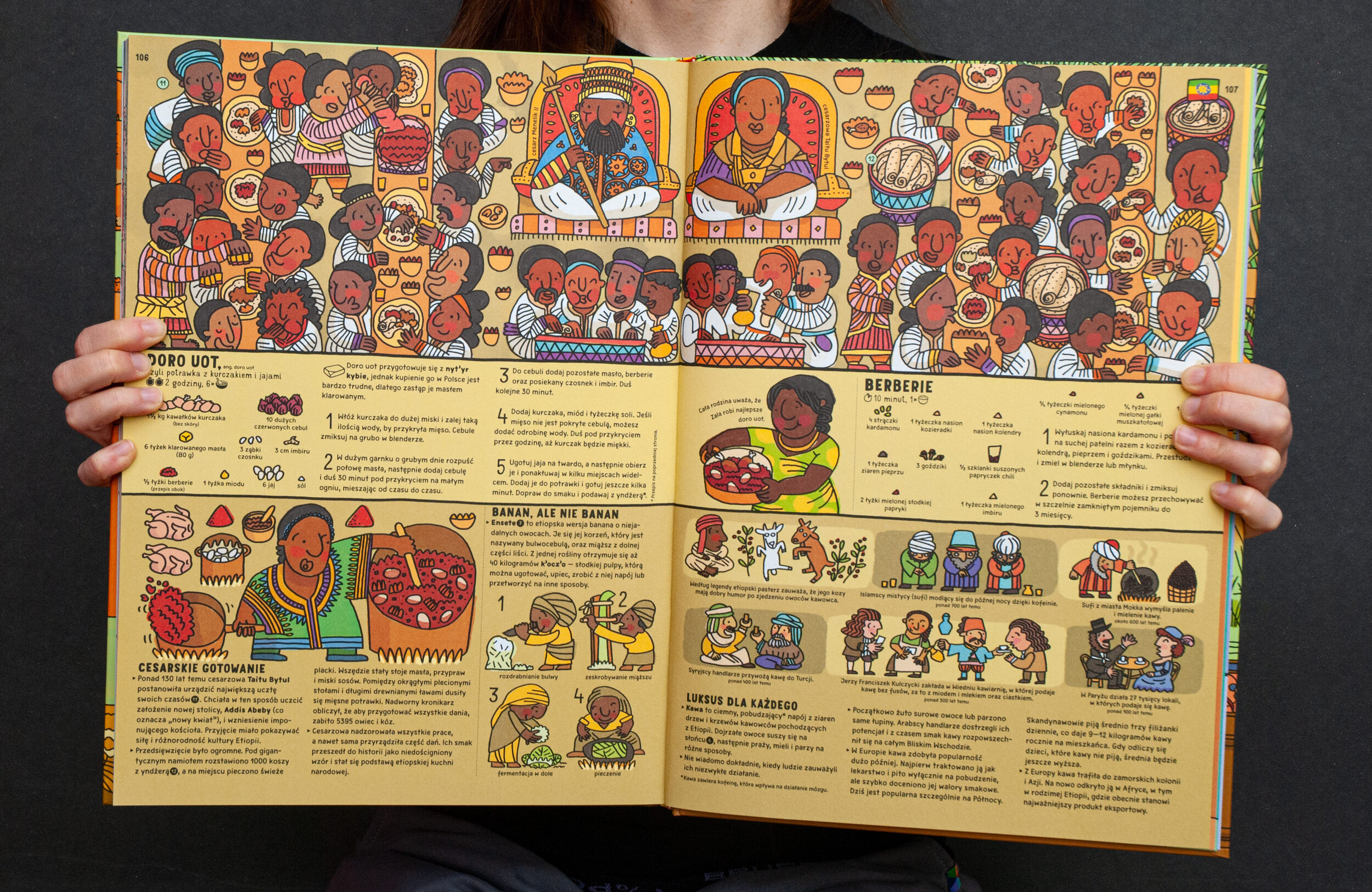

We returned to the project over a year later, erased everything and started again. We stuck to original concept of dividing book by countries. We wanted to focus on the history of food and how it shaped early civilizations and modern societies. Recipes would be added as examples of described products, traditions, or culinary techniques, and they would not be the main course of the book. Layout was designed around very rigorous grid to avoid the chaos we previously struggled with. Every spread would have a panoramic illustration at the top of the page and a recipe placed in a grid below it. Texts for each country would start with an introduction occupying 2–3 grid modules. Each country would consist of 4–7 short stories sharing a common theme or a set of distinctive or representative topics.

After few months Natalia combined a list of potential recipes (see below for details on making the book). We started with Mexico, Egypt, and Hungary and decided to present it to Dwie Siostry. Their reaction was overwhelmingly positive. Those three countries didn’t change since then (of course some changes in text were necessary) and finally we had successful concept for the book.

How the sausage was made

After establishing the definitive structure and look of the book all we had to do was to sit enough hours to finish it. We divided work into four stages: preparing and testing the recipes, research, writing and drawing.

Recipes

Our first list was closed back in 2014, when we were working with Natalia on the first version of the book. We wanted to have at least two recipes for each country. We knew that this selection would be the most controversial part of the book. There are so many great dishes that are representative for a specific regions, but the representation wasn’t our main concern. The recipes were supposed to illustrate topics assigned to each country and they had to be a great choice for a family cooking.

This is why, when deciding on potential candidates, we paid attention to:

Their popularity in the countries we placed them in.

If we wrote about the key ingredients needed for the recipe.

Are they easy to prepare (this book is not only for cooking enthusiasts).

Can you buy ingredients crucial to prepare the dish even if you live in another country.

We ended up with a long list of great dishes. Later on a lot of them had to be replaced after we finished the research, but it was a good start.

Then Natalia had to create easy reproductions of the recipes. For each dish she collected dozens of traditional variations and distilled them to the most faithful and easy to make adaptations.

Then the testing phase came. After Natalia did her initial trials we prepared almost all of the dishes together, and then on our own. Of course that was not enough. Natalia wanted to test them among young beginners and old veterans, so a lot of friends were involved in the process. The hardest part was checking if we got the taste just right. Obviously almost all of these dishes have endless variations – they are classics after all – but we didn’t want to have any misfires. The ones that we had tasted in the country of origin were easy. For others we visited restaurants run by chefs whose renown we could trust. Finally, if possible, Natalia cooked some of them to people born and raised in a specific region. I think the most satisfying reaction was when a Greek friend said that Natalia’s version tasted exactly like it was made by his mother.

Research

This is the first book we wrote and drew for which key work – the research – was made by someone else. The idea was quite simple. Natalia would go through few very heavy books in search of main topics from a specific region (not just single country). Then, together, we would decide to which countries those topics should be assigned. After that, Natalia would dig deeper into selected countries, trying to find more specific sources to create a subset of smaller topics. This process would produce a long Google document for each country, containing a list of topics, detailed descriptions, images, and quotes from trusted sources. Armed with this knowledge we would do the final selection, choose a theme for the country and do some reading of our own.

Selected stories and final versions of recipes would be distributed within a grid taking exactly 4 pages. In an oversized book it was enough space to give an interesting sample of traditions from different regions without skipping the key products (wheat, rice, corn, cocoa, etc.), culinary discoveries (how to brew coffee, how to make tofu) or events when food changed the course of human history (domestication of important plants and animals, establishing trade roads to import regional goods).

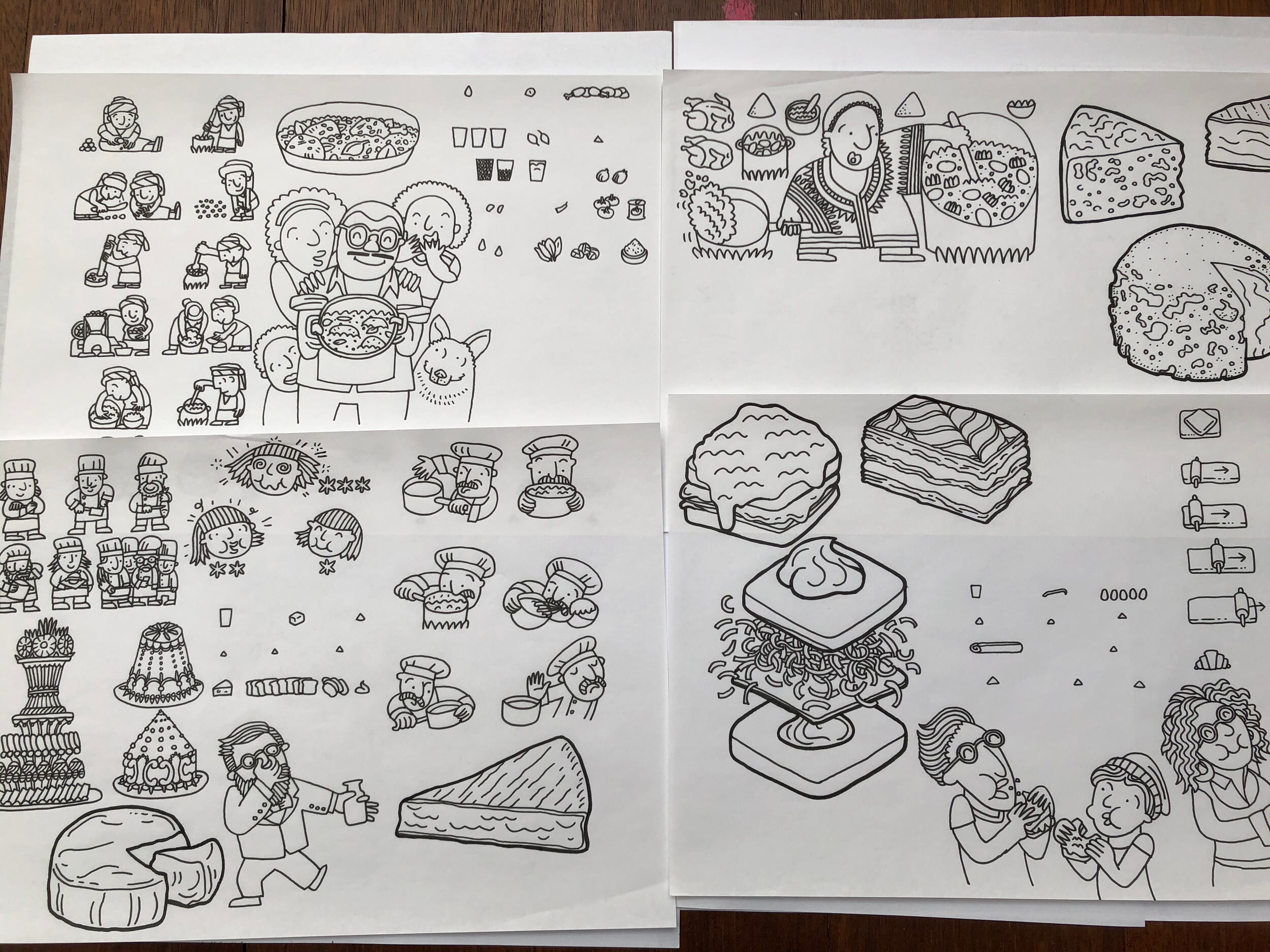

Writing and drawing

After all this preliminary work was done, we selected one country and wrote all the texts assigned to it. We knew exactly how many modules we had to fill and where would the drawings go. When Aleksandra or Daniel would write the final text for a country, others (including Natalia) would read it and give feedback. With this done we would print pages from the book with roughly final texts on them – this way we had something like a blank form that could be filled with drawings.

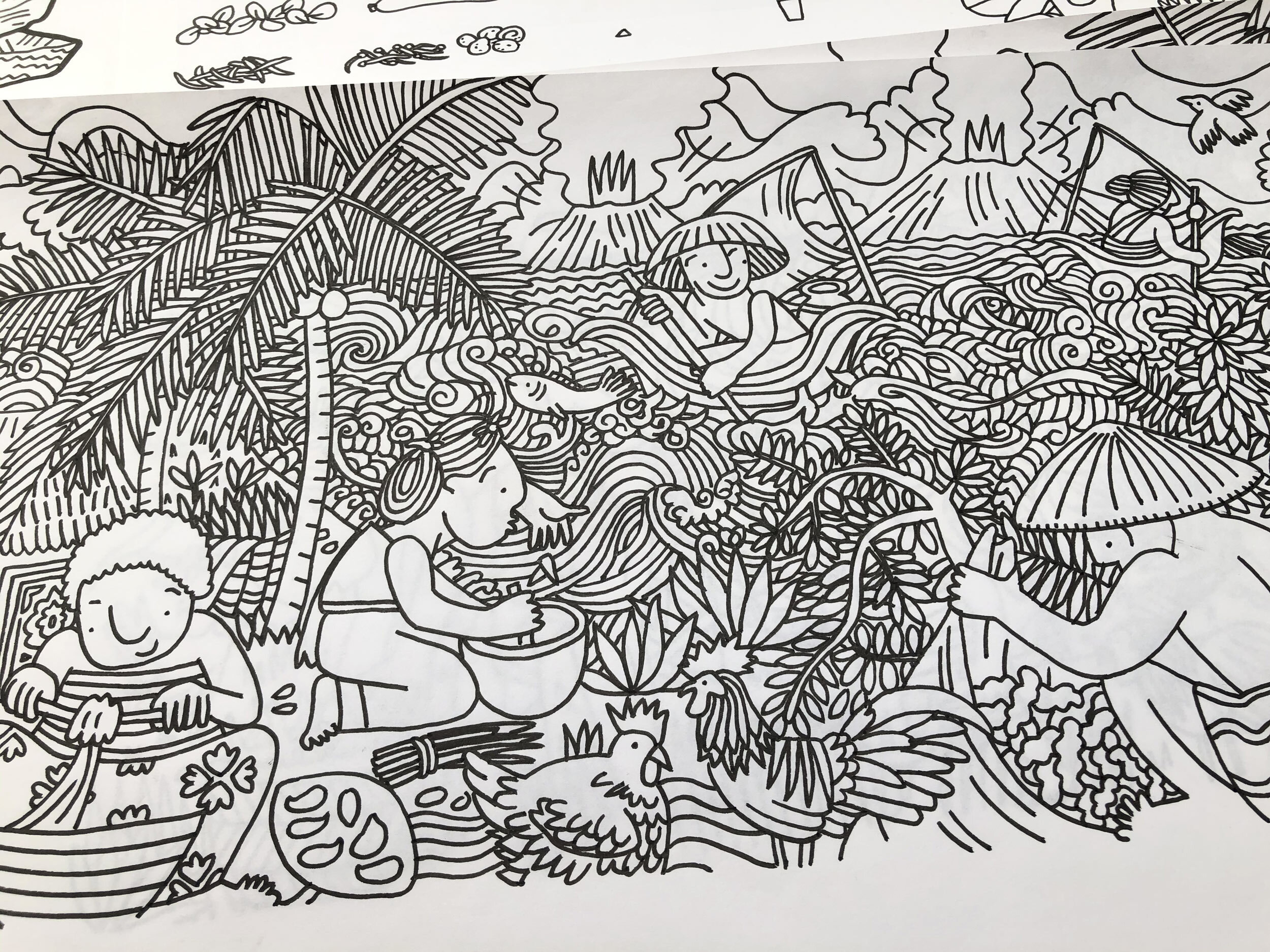

First we would draw all of the smaller drawings for a single country directly on the printed pages. As usual we used pencils for that stage. If we were satisfied with all the small drawings we would take a thin (45gsm) layout paper and a 0.8 mm black UniPin pen and trace the final drawing. Those would be scanned and positioned around earlier prepared blocks of text. The colours would be added in Photoshop using our custom made brushes. With this part finished, the only thing left was to draw the panoramas, and to assign numbers to elements in the pictures that were mentioned in the text.

Excluding research and testing recipes the process of writing and drawing a single country took a couple of weeks.

In search of inspiration

In most of our books you can find quotes or references to the history of art. For example, the thief that you can follow in Welcome to Mamoko is stealing The Scream by Edvard Munch (which was actually stolen at the time we were drawing the book). This time we wanted to create an homage to our favourite painters, and sometimes even specific masterpieces.

All of the historical panoramas in Daj gryza are inspired by amazing paintings, murals, graphics, reliefs, mosaics and ceramics. For example, in Indonesia we were enchanted by amazing work of a traditional Balinese painter – Ida Bagus Made Poleng. In Norway, the sky and general atmosphere are a reference to The Scream by Edvard Munch (yes, again, we really like this painting). The first Japanese spread is our praise to unbearably good series of Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji by Katsushika Hokusai. In Italy, the first panorama mixes styles of different Early Renaissance painters, while the second one is an obvious reference to The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci.

Content verification and editing

Almost all of our books created between 2008 and 2020 were edited by wonderful Maciej Byliniak. We do not always agree, one can even say that we sometimes strongly disagree, but I think we understand each other pretty well. This time Maciej couldn’t be the leading editor and we worked with Dominika Cieśla-Szymańska. Maciej still worked on some parts of the book, but the day-to-day responsibilities rested in Dominika’s hands. Additionally, there were two other editors involved in the process. They did the first review which was later sifted by Dominika, before getting to us.

Our publisher also asked 21 specialists, whose interests span from the history of ancient civilizations to modern Nigerian cinema, to verify and give a fresh feedback on specific parts of the book.

After that, Małgorzata Kuśnierz was asked to proofread the whole book. Some final edits were applied and we could start working on index and chronological table of content.

Help me find what I need

The last big thing on our list was creating the table of content. This book is filled with a wide range of information. Without help it might not be easy to find exactly what you’re looking for. As a rule, we wouldn’t mind it: we would even prefer readers to flip through the pages and occasionally stumble on a new topic, forgetting what they were looking for in the first place. But, as exciting those accidental discoveries would be, not being able to find a specific information would not be as enjoyable.

That is why we prepared four very different tables of content:

A list of countries with corresponding page numbers (located on the first endpaper)

A list of recipes included in the book (located next to the title page).

A chronological table of content including almost 200 events mentioned in the book (two last spreads, just before the endpaper).

A traditional index listing references to over 500 topics (the closing endpaper).

The editors wrote a nice introduction to instruct readers how to use those lists (and also, forecasting potential complains, an explanation why not every dish is included in the book). We think that this is our first book with such proper introduction since D.O.M.E.K..

Animation

In the harsh times of Covid-19, as a tiny help with promoting the book on social media, we promised Kasia from Dwie Siostry to prepare few short videos with us reading the book. Because reading picture books without showing any pictures doesn’t really make sense, we made three very simple animations:

Foreign editions

French, Cuisines du Monde, Gallimard Jeunesse, ISBN: 2023, 978-2-07-519407-5

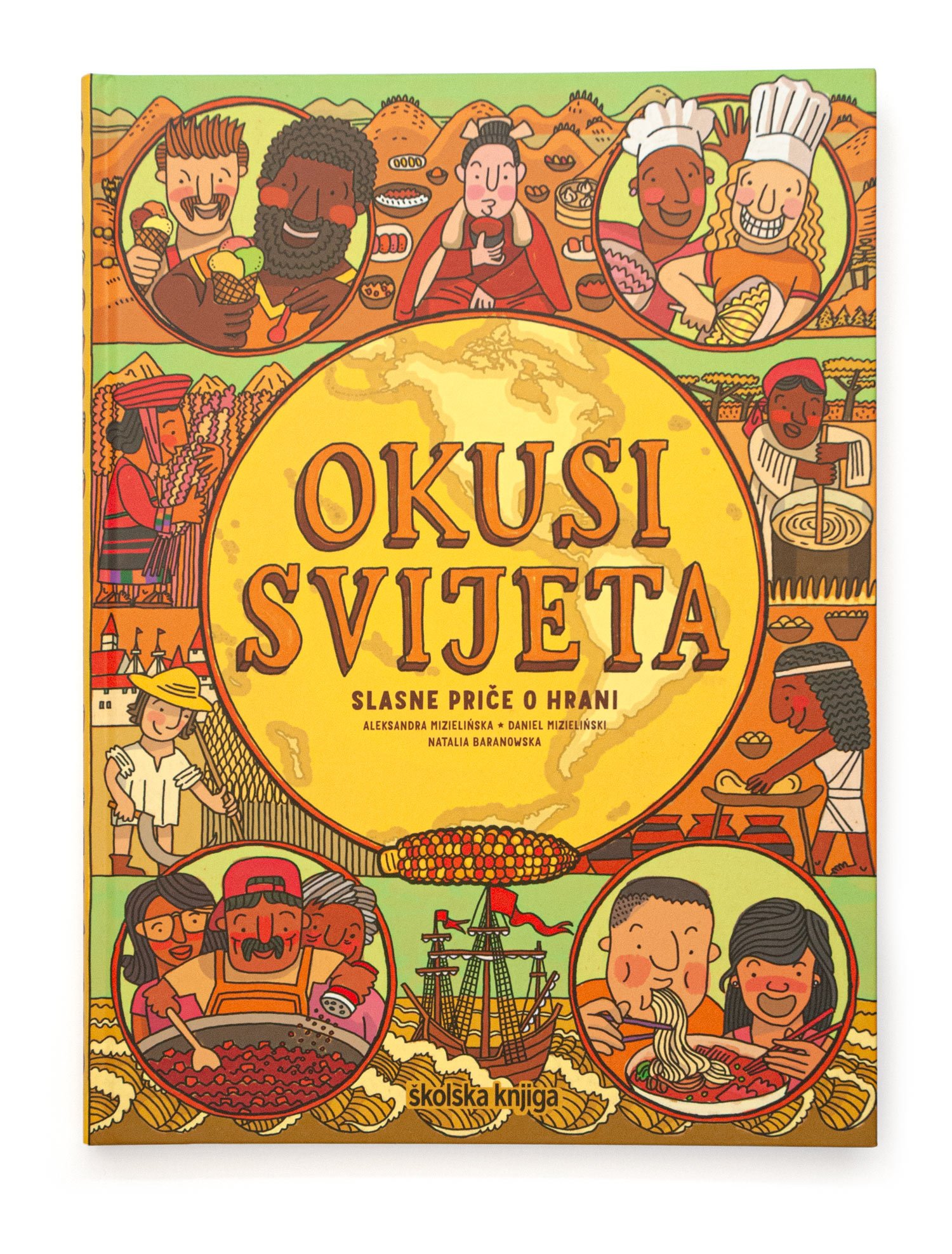

Croatian, Okusi svijeta, Školska knjiga, 2023, ISBN: 978-953-0-62279-1

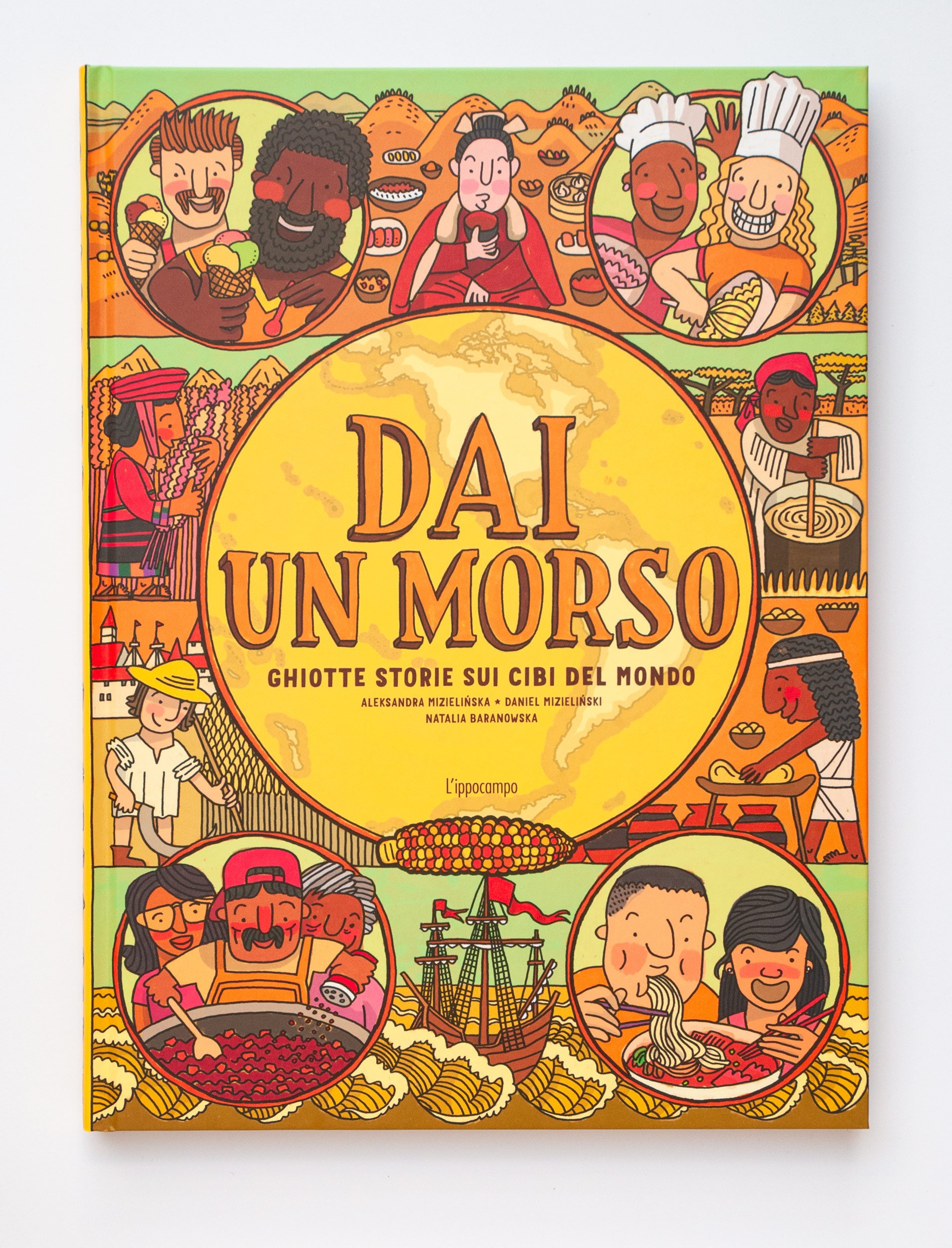

Italian, Dai un morso, L'Ippocampo, Milano, 2021, ISBN: 978-88-6722-665-8

Greek, Δωσε μου μια μπουκια, Εκδοσεις πατακη, 2021, ISBN: 978-960-16-9615-7

Spanish, Dame un bocado, Maeva young (Ediciones Maeva, S.A.), 2021, ISBN: 978-84-18184-74-1

Dutch, De wereld op je bord, Lannoo, 2021, ISBN: 978-94-014-7932-5

German, Alle Welt zu Tisch, Moritz Verlag, 2021, ISBN: 978-3-89565-420-6

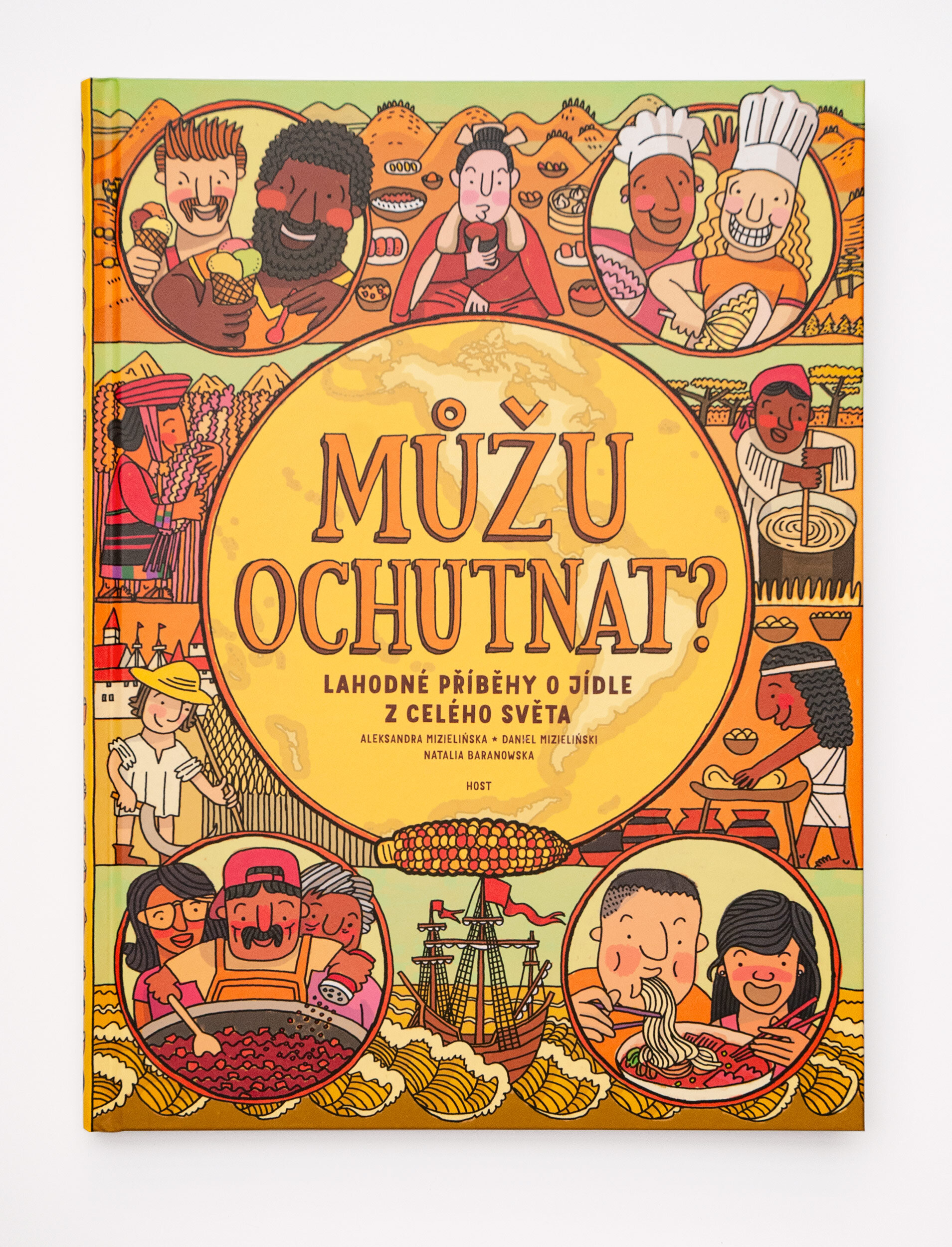

Czech, Můžu ochutnat?, Host, 2021, ISBN: 978-80-275-0749-8

Portuguese (BR), Posso provar?, Editora WMF Martins Fontes Ltda., 2022, ISBN: 978-85-469-0372-6

English, Take a bite, Big Picture Press, 2022, ISBN: 978-1-80078-288-4

Traditional Chinese, 好想吃一口, Global Kids, 2022, ISBN: 978-986-525-464-3

Japanese, 世界の国から いただきます!, Tokuma Shoten Publishing Co., 2022, ISBN: 978-4-19-865583-9

Korean, 한입에 쏙!, Ggumsun Publishing Co, 2024, ISBN: 979-11-92352-04-6

Simplified Chinese, 世界美食大书, Ronshin, 2025, ISBN: 978-7-305-28668-1

You can find a Google Sheet with a list of all our foreign editions here.

The best gift

Every Christmas our friend and co-worker Zosia Frankowska prepares gingerbreads for her friends. In 2020, a month after Daj gryza premiere she gave as a huge bundle of very familiar looking gingerbreads. It would be a crime just to eat them without posting some photos.

Covid-19

This is our second big book that was launched during the Covid-19 outbreak. Which Way to Yellowstone? premiered in late March 2020, about two weeks after Polish government closed the whole country. We still don’t know how this will affect our industry. Which Way to Yellowstone? seems to be doing fine and as of December 2020, there are already 4 foreign editions and another 4 in the making.

Of course it’s not the best time to launch a new book, especially one that you’ve been working on for so long, and published just after finishing another book of the same magnitude. We just hope that this mess will end soon, and in the meantime, kids and adults can have some more fun with our books.